Photo credit: Internet Archive Book Images via Foter.com / No known copyright restrictions

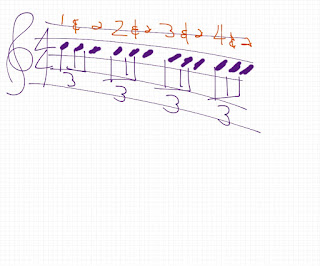

Other examples are a quintolet, which is five notes in the time of four of the same kind of note. A sextolet, six notes in the time of four of the same note. A septolet, seven notes in the time of four of the same kind of note and a triplet, three notes in the time of two.

A duplet and quadruplet are only found in compound time.

A triplet, quintolet, sextolet and septolet are found in simple time.

Photo credit: ljguitar via Foter.com / CC BY

Baxter, Harry and Michael Baxter. The Right Way To Read Music. Tadworth: Right Way, 1993. Print, pp. 74 to 76.